January, 25 1998…

So you want me to tell you the story of my life.

Yes. Like I said, that’s what I do.

You interview people.

I collect lives. Books, interviews, newspapers, magazines…. I take it you’re familiar.

You’ll need a lot of pages for my story.

No problem. I brought plenty: Notebooks.

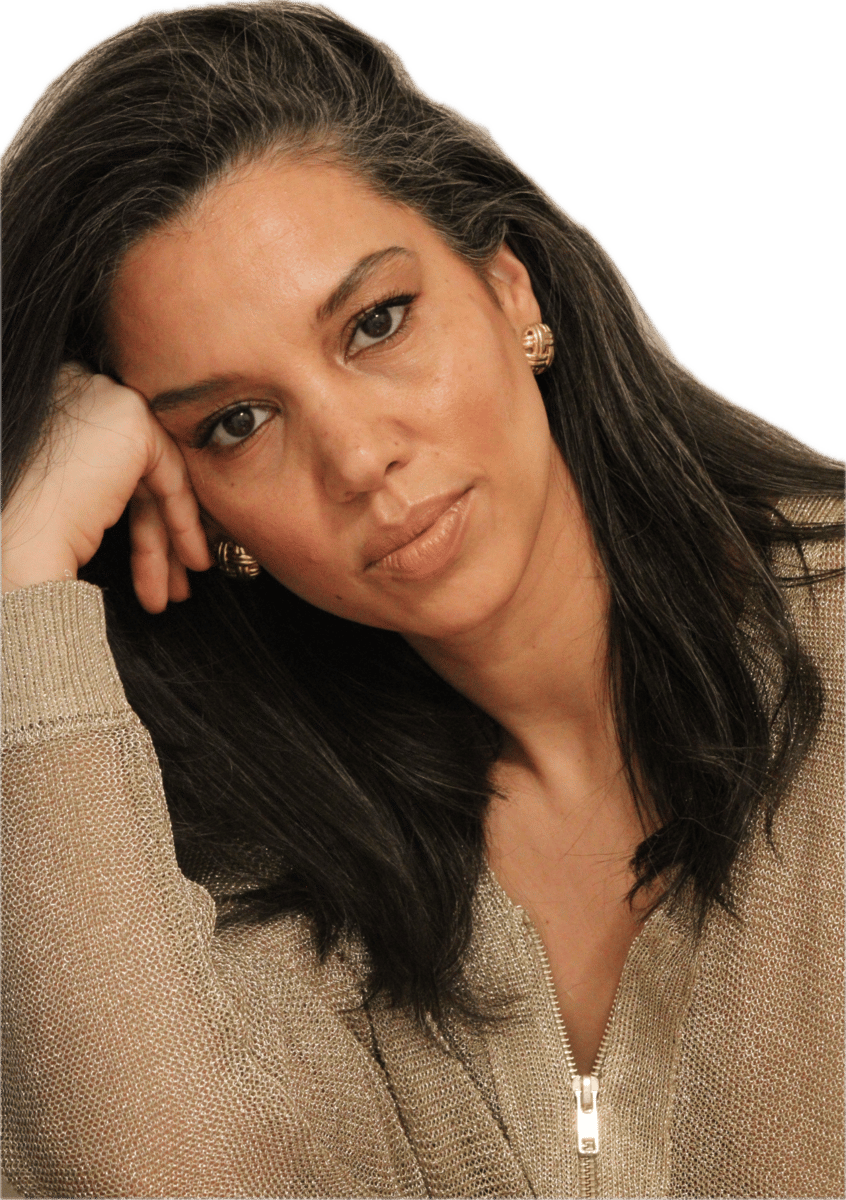

She watched him for a moment: - You followed me here, didn’t you.

Yes. I suppose I did.

Why.

You seemed interesting.

There was a brief silence.

So, she said, shall we get started.

What do you do, he asked.

I’m a Realtor.

He hesitated: - You say that without shame…

Absolutely.

March, 13 1995

The journalist was deep in the municipal archives, researching something dull and procedural—railway permits, zoning disputes, a forgotten labor strike. The kind of story that never makes a person famous but pays the rent. The kind of work that exists almost entirely in the negative space of history, where nothing explodes and no one confesses and the most dramatic moment is a clerk admitting that a ledger was “probably misfiled sometime in the 40s.”

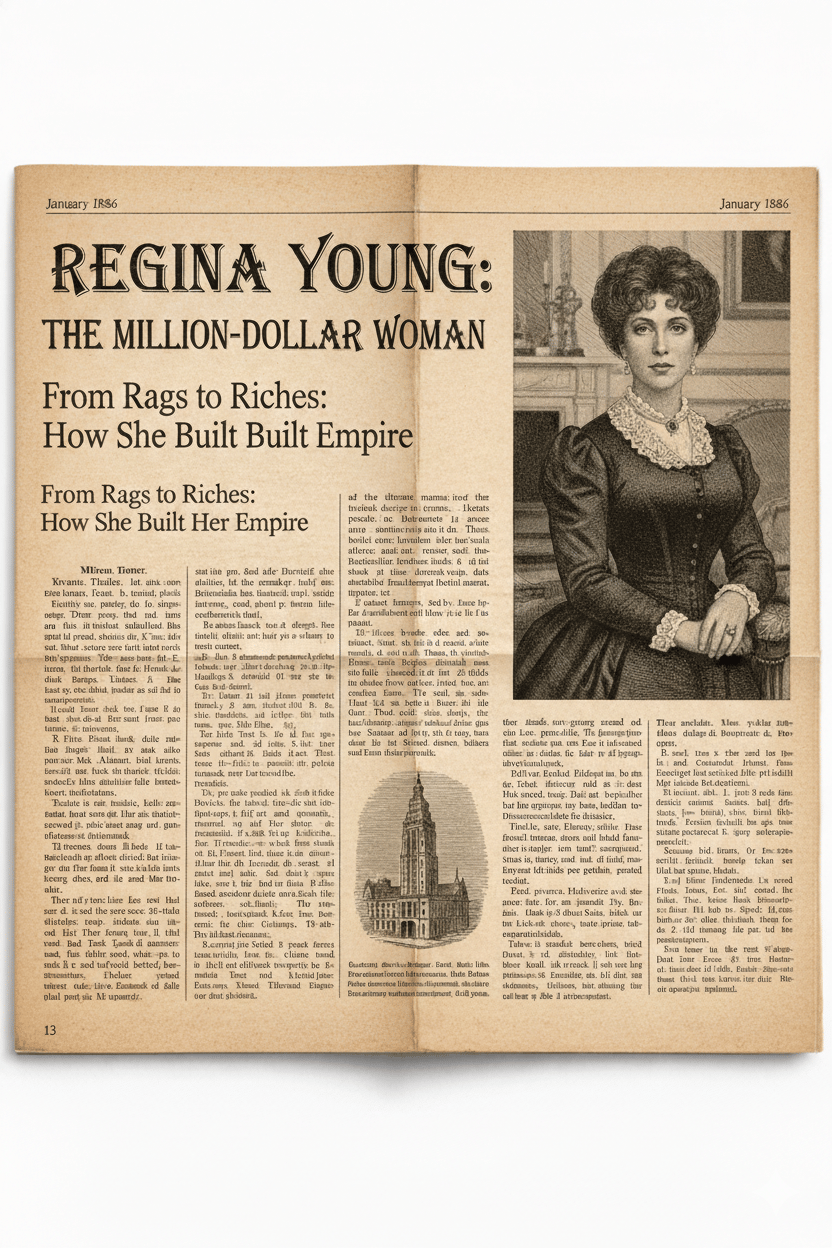

That’s when he saw the headline.

Folded into a brittle stack of yellowed papers, ink bleeding softly into the fibers in that way old newsprint does when it has long since surrendered any ambition of being read again, was a page that did not announce itself so much as wait. It wasn’t screaming. It wasn’t framed. It wasn’t even centered correctly.

REGINA YOUNG

The first self-made woman of the Republic

1886

His first thought—unremarkable, reflexive—was that it had to be satire. Or hyperbole. Or one of those late-19th-century editorials that mistook economic competence for moral superiority and liked to crown industrialists the way children crown ants with blades of grass. He assumed there would be a punchline further down the page. Or at least a tone shift. Something to signal irony.

There wasn’t.

The article was short. Almost curt. As if the writer resented having to explain her at all. It listed land deals the way one lists weather patterns—rail corridors secured, parcels consolidated, developments quietly absorbed. No adjectives beyond the strictly necessary. No awe. No outrage. Just fact arranged next to fact in a manner that suggested inevitability rather than achievement. It mentioned her accent, once, clinically. Mentioned her discipline, in the way one might note that a machine required regular oiling. Mentioned, with a faint editorial shrug, her refusal to marry.

And then—once, buried mid-paragraph, as though it had slipped past the copy editor unnoticed—it called her an immigrant.

The journalist paused there longer than he meant to. Not because the word was shocking, exactly, but because of how little weight it seemed to carry in the sentence. No qualifier. No narrative of struggle. No redemption arc. Just a descriptor, like height.

The photograph stopped him…

The face was clear. Composed. The expression neutral in that unsettling way that suggests a person who understands exactly where they are and has no interest in reassuring anyone else about it. The lighting was flat. The posture correct. The eyes direct without being challenging. He was sure he had seent her before… but nowhere.

It was the sort of face you might pass on the street without noticing—except that once you had noticed it, it would feel wrong not to recognize it again.

He felt, briefly, the mild disorientation that comes when something fits too neatly into memory despite having no business being there. The kind of familiarity usually reserved for people you grew up with or loved or disliked intensely, none of which applied. Not that he could remember. His shoe laces were untied and he seemed to not be able to focus any longer. He needed to research some thing about tax laws for a paper he was writing for someone. he forget his name. But at $100 a paper… He had to return to work too.

He took our his camera and tried to take a photograph of this article. He told himself he’d look into it later. He told himself lots of things that afternoon. But all he could think of was this odd woman. How he never heard of her. But knew her so well…

Then he slid the paper back into the stack, returned to his desk, his permits and disputes, and finished the workday the way most workdays finish: quietly, without revelation, convinced—incorrectly—that the important part had already passed.

June, 5th 1997

The dentist’s office was aggressively normal. The carpet was muted, the kind designed not to show stains. Diplomas hung on the wall, their frames faded to the color of old teeth. A fish tank hummed softly in the corner, its occupants circling with the patience of creatures that understood their purpose was decorative. Somewhere behind the front desk, a radio played a talk show that never seemed to arrive at its point.

He checked in, sat down, and chose a chair that didn’t wobble. The room rewarded this decision by remaining exactly the same.

A low table held a scatter of magazines—some current, some inexplicably old—selected with the same vague logic dentists everywhere seemed to share: inoffensive, aspirational, disposable. He reached without looking and picked one up.

The date on the cover stopped him.

It sat there plainly, without apology, as if it were perfectly reasonable for a -decade-old magazine to circulate among pamphlets about fluoride treatments. The headlines were familiar, almost comforting: politics, weight loss, money. History reduced to fonts and colors.

He flipped a few pages.

Then he saw her.

There was no jolt, no spike of alarm. Just the quiet sensation of having arrived somewhere he had already been. The profile took up a full page, laid out with confidence.

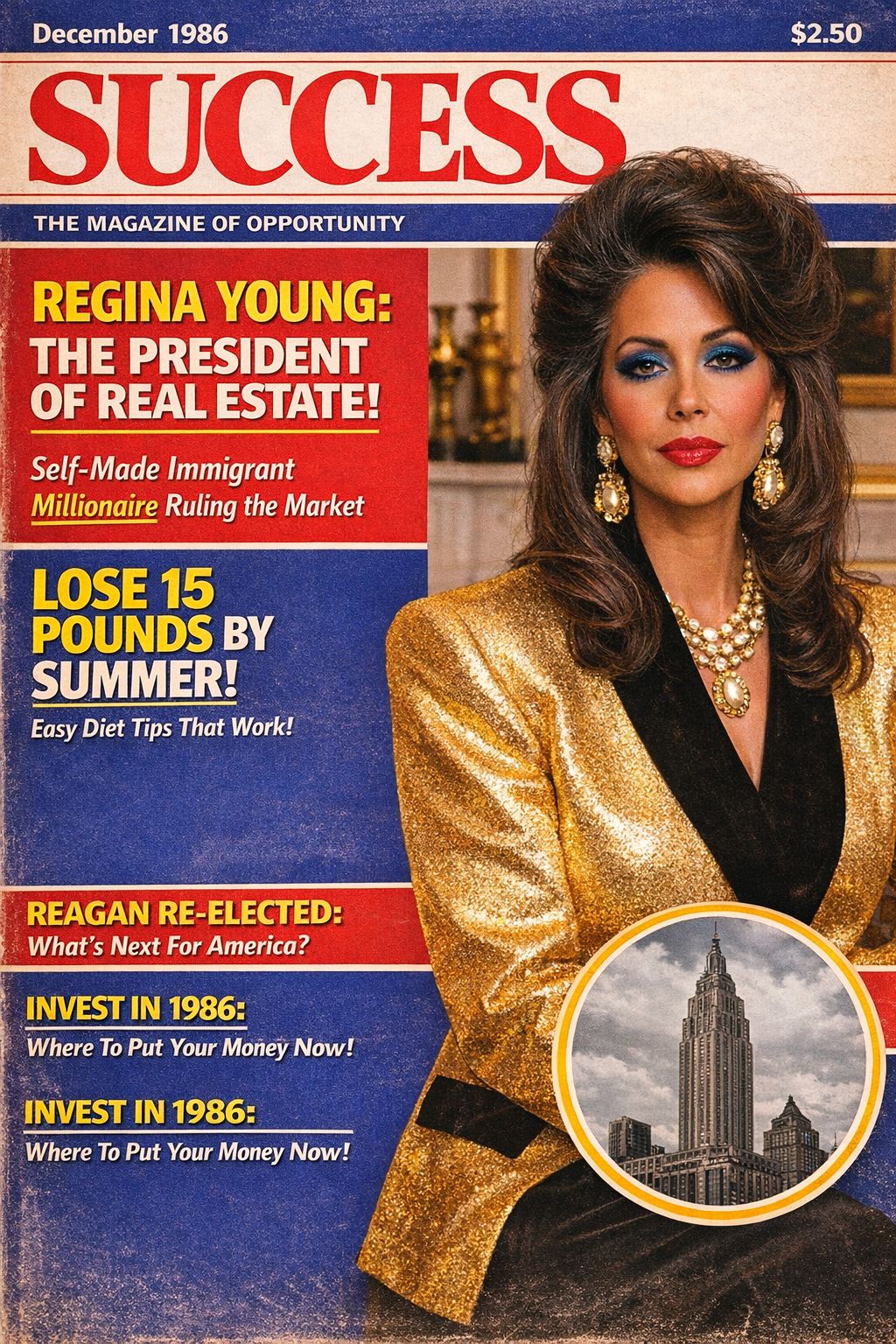

REGINA YOUNG: THE MOST POWERFUL REALTOR IN AMERICA.

Self-made. Immigrant. Unmarried.

The photograph was different from the one in the archive. The styling was sharper, more contemporary. But the face was exact. Not similar. Not reminiscent. Exact. The same eyes, the same mouth, the same expression of neutral authority that refused to perform gratitude or ambition.

He turned the page back. Then forward again. He checked the date. The byline. He ran his thumb along the edge of the magazine, as though it might reveal itself to be a reprint or a mistake.

The article praised her efficiency and her instincts. It described her ability to move quietly through systems built by louder men. It presented her as new, as emerging, as someone who had come from nowhere and arrived fully formed.

It mentioned her accent. It mentioned her discipline. It mentioned her refusal to marry.

And once—without emphasis—it called her an immigrant.

There was no age listed. No childhood. No indication of an ending. Only momentum.

He became aware of how tightly he was holding the magazine. Of the steady hum of the fish tank. Of a hygienist calling a name that was not his. No one else in the room appeared disturbed by the bending of time on the coffee table between them.

He closed the magazine and set it back where he’d found it. The room did not react.

For the first time that day, he did not tell himself he would look into it later. He understood, without knowing how, that later had already been decided.

“Perhaps you'd like another cigarette?

I would…

I don’t think it will kill you… - he says under his breathe, waiting for a reaction.

She takes the cigarette. The lighter clicks once, twice, then cooperates. For a second the flame reflects in her eyes, sharp and practiced.

People always confuse cause with timing, she says, drawing in - Smoke leaves her slowly, as if it's been instructed to behave.

So you're not worried? he asked.

She smiles—not kindly, not cruelly. Precisely.

-Worried is for people who think the end is negotiable.

She taps ash into an ashtray that looks ceremonial, like it's been waiting for this exact gesture for decades.

-Most people stop for their health, they say. Or their families.

She leans back, crossing her legs, reclaiming the room inch by inch. Most people stop because they believe stopping changes the story.

Ask it, she says: The question you rehearsed. The one that made you follow me here

To Be Continued…